Corollaries in Siteswap

Lack of Intro

Siteswap, the mathematical notation for juggling is relatively well researched and well understood. Rather than start this blog post with a few paragraphs about its history and some simple examples, I’m going to provide some links that do that and jump right into the meat.

- An hour long and comprehensive lecture at Cornell

- A comprehensive wiki article

- A well written paper proving some fundamental results

- A more modern book proving additional theorems

Validation of Vanilla Siteswaps

It is well known that a vanilla siteswap which does not average to an integer is invalid. What is less well known is why certain vanilla siteswaps that average to an integer are invalid.

The premise of siteswap is that discretized time into a number of evenly space units. Every throw and every catch must occur at one of those units. When we say that a pattern is valid we really mean that the indegree each time unit (the number of objects being caught then) is equal to the outdegree (the number of objects being thrown then). In vanilla siteswap, that means at every time unit, at most one ball can be caught. Thus, a pattern is forbidden if there exist two throws that land at the same time. We can express this formally as follows.

For all siteswaps \(a_1 a_2 \cdots a_n\), \(\forall x \in \{1 \cdots n\} \forall y \in \{1 \cdots n\}, x \ne y \implies a_x + x \not \equiv a_y + y \pmod n\)

If we wanted to verify these pairwise relations individually, we would need to do quadratically many checks. A cheaper way to to note that the above statement is equivalent to saying that the set \(\{a_x + x\} \pmod n\) is equivalent to a permutation of the numbers 0 through \(n-1\). The following code takes a list of integers and does just that.

1 def verify_vanilla(siteswap):

2 multiplicity = [False] * len(siteswap);

3 for i in range (0, len(siteswap)):

4 index = (siteswap[i]+i) % len(siteswap)

5 if multiplicity[index]:

6 return False

7 multiplicity[index] = True

8 return True

Generating New Siteswaps From Existing Ones

From this algorithm for verifying a siteswap, we can easily define several ways of mutating a siteswap without compromising its validity.

Add 1 to Every Number

If it is the case that \({a_x + x} \pmod n\) is a permutation of the set \(\{0 \cdots n-1\}\) then adding one to each \(a_x\) will not modify this property.

- 423 becomes 534

- 633 becomes 744

If all of the values of the siteswap are greater than 0, this process work in reverse too. You can subtract 1 from each number in a valid siteswap to generate another valid siteswap.

Add Pattern Length to One Number

Similarly, added \(n\) to one \(a_x\) will not change its value modulo n. Therefore the siteswap will still be valid.

- 441 becomes 4, 741 or 714

- 71 becomes 91 and 73

If any value in the siteswap is greater than the pattern length then this process can be done in reverse as well. Subtracting the pattern length from any value in a valid siteswap will produce another valid siteswap so long as all the value remain positive.

Swap Sites of Two Throws

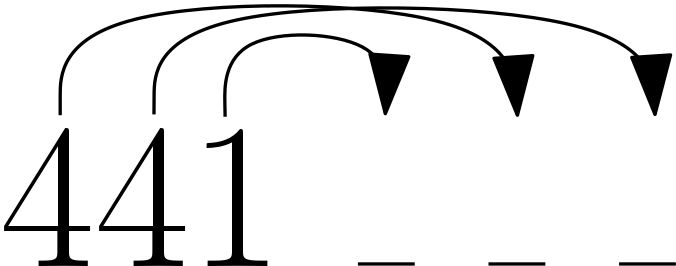

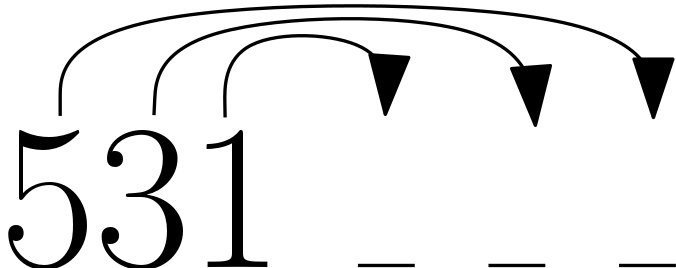

The above two mutation methods both modify the number of objects being juggled; This strategy does not. Lets start with an example, 441.

In this image shows which time unit each throw will land on. To modify this siteswap, we are going to swap the ending locations of the two 4s. The first of our three throws now goes forward 5, the second throw goes forward 3, and the third is unmodified and goes forward 1. We have just discovered the patter 531.

More generally, if we select two throws \(a_i\) and \(a_j\), such that \(i < j\) and \(a_i + i < j\), then we can replace $a_i$ with \(a_j + j - i\) and \(a_j\) with \(a_i + i - j\) - effectively swapping the sites they land at. This method of pattern generation is the origin of the name siteswap.

Extending to Multiplex Siteswaps

We can model multiplex siteswaps very similarly to vanilla siteswaps by relaxing the condition that indegree and outdegree can be at most 1. We now only require that they be equal at each time unit. This means that much of the reasoning that we applied to vanilla siteswaps is still applicable. Unfortunately our easy to describe mutation strategies can’t be said as easily anymore.

If we can identify a subset of the pattern which is a valid vanilla pattern then we can increment every element of that subset and get a valid pattern. For example [43]41 contains 441 so we can create the pattern [53]52. I’m actually not sure if this is always possible - probably not.

When counting patten length we count a multiplex as a single throw. Then the strategy of adding pattern length to any one number still works as before. For example 23[34] goes to 53[34], 26[34], 23[46] and 23[37] all of which are valid 4 ball multiplex patterns.

Swapping sites works exactly as before. We pick two throws where the first doesn’t doesn’t land before the second is thrown and swap their sites.

Extending to Sync Siteswaps

Sync siteswaps are doubled in a way that is subtle but convenient. I’ll probably go into it more in another blog post. On the topic of mutating sync siteswaps though, we need to add 2 to every number which increases the total number of balls by 2. For example (4x,2x) goes to (6x,4x)

When counting pattern length, each (a,b) throw counts as two throws. For example (4,2x)(2x,4) maps to (8,2x)(2x,4) or (4,6x)(2x,4).

Swapping sites works as before but with a more complicated notion of a site. At each time unit there is a left site and a right site and we can swap between time units or within time units.

Understanding Transitions

When describing a pattern that isn’t in ground state, jugglers sometimes list the sequence of throws to enter it from ground state and the sequence of throws to exit it.

Entry + Exit is a Valid Siteswap

A fact that isn’t commonly known is that the concatenation of the entry and exit sequences is always a valid siteswap. If we think about siteswaps as cycles in a state machine, the reason for this is apparent. The transitions are paths from a node in one cycle to a node in the other and back. Therefore the concatenation of the two is a cycle in the graph as well and must also be a valid siteswap. Furthermore if the starting pattern was ground state then the generated Entry+Exit siteswap will also be ground state.

This fact is less useful for generating new siteswaps than it is for quickly computing the exit from a siteswap of known entry. For example to enter 933 from a 5 ball cascade we can throw a 7. A five ball ground state move that starts with 7 is 744. Therefore 44 is a valid exit from 933 back to 5.

We can repeat this process to generate other transitions. A five ball ground state siteswap that ends in 44 is 94444. Therefore we can also enter 933 from 5 with a 944.

How to get an initial transition between two patterns is a somewhat interesting question that I think I’ll leave for another blog post.