Magnetic Hinge Arrangement

Background

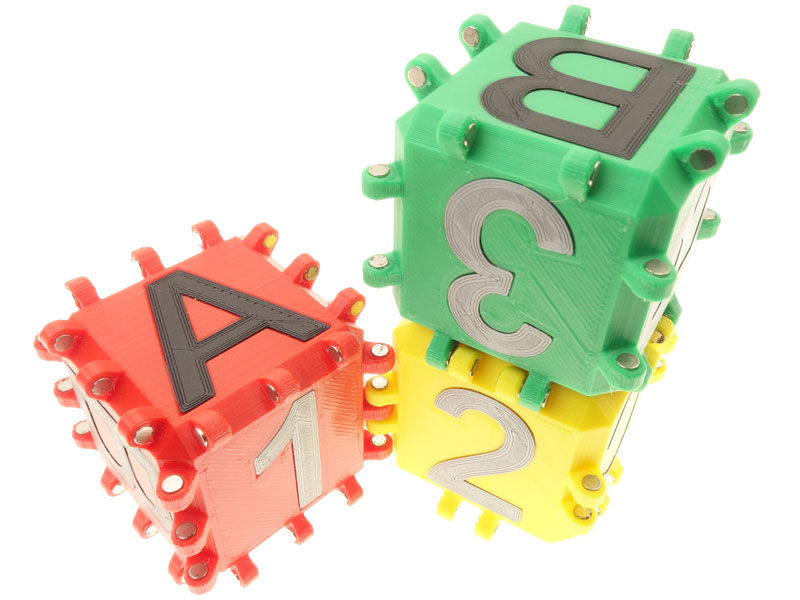

Yesterday, Oskar van Deventer posted a video of a new puzzle he’d developed. If you watch the video, you’ll see three cubes where each one has magnetic protrusions along each edge. The protrusions on each cube are arranged so that when any pair of cubes are connected edge-to-edge, they form a magnetic hinge.

Oskar’s puzzle has three cubes, but I was curious what arrangements one might use if designing this puzzle with an arbitrary number of cubes. This boils down to the question: Arrange the numbers 1-N into a sequence with duplicates allowed such that every pair of numbers is adjacent somewhere in the sequence.

Analysis

We can put some upper and lower bounds on the length of a minimal sequence as follows:

Upper bound: given N objects, there are C(N,2) = N*(N-1)/2 pairs that need to be accounted for. One sequence that satisfies our question is “all pairs printed one after another”. For example, when n=4, our sequence might be 121314232434. This sequence has length N*(N-1).

Lower bound: Given N objects, there are C(N,2) pairs that need to be accounted for. Each element we add to the sequence creates one new pair. Therefore, a sequence containing C(N,2) pairs must be at least 1+C(N,2) elements long.

When N is even, I believe the lower bound cannot be achieved. This is because most elements don’t appear at either end of the sequence so they have an even number of neighbors. But when N is even, an odd number of those are mandatory and one is extra. I believe the sum of these “extra” neighbors makes it impossible to get to the lower bound sequence length.

Embracing Randomness

Rather than try to be clever with constructing these sequences, I decided to do a whole lot of guess, test, and revise. I wrote a bit of C++ to do so:

The first one generates sequences made up of |symbols| different values and of length |len|.

std::vector<int> make_candidate(int symbols, int len) {

std::vector<int> ret(len, 0);

for (int i = 0; i < len; ++i) {

ret[i] = rand() % symbols;

}

return ret;

}

The next one checks if a sequence satisfies our condition. It stores each pair in an unordered set by hashing it. Then it checks if enough pairs have been found by comparing against a global constexpr that was computed based on the number of symbols being used (also constexpr).

bool check_candidate (const std::vector<int>& v) {

std::unordered_set<int> seen;

for (int i = 0; i < v.size() - 1; ++i) {

if (v[i] != v[i+1]) {

int low = std::min(v[i], v[i+1]);

int high = std::max(v[i], v[i+1]);

seen.insert(100*high + low);

}

}

return seen.size() >= pairs;

}

From there, I just ran trials continuously until I got results I liked. By tweaking the lengths of the sequences I was generating, I could slowly hone in on the optimal length.

A nice feature of this approach is that nothing needs to be remembered from trial to trial. This means the program uses very little memory and can be left running as long as I am willing to wait.

For small values of N, this worked quite well. But as N got to 7 or 8, valid sequences became harder and harder to find. I decided to up the length of sequence I was checking to increase the chances of finding valid sequences but add some postprocessing to try to get results that were as good as possible.

Optimizing Random Output

I came up with two simple ways to shorten a valid sequence.

The first was to filter out letters that were adjacent to themselves. This doesn’t effect correctness so it’s always OK to to do.

The second was to test the sequences with the first/last elements removed. In a lot of cases, the first pair would also appear elsewhere in the sequence so removing the first element was fine. Likewise with the last pair and the last element.

Results

By combining these techniques and doing a lot of trials, I came up with the following results:

4: 12324314

5: 12342541531 (hits lower bound)

6: 123453463142615256

7: 1234537257182413847851 (hits lower bound)

8: 12342562754783581641748673158263

9: 1234354256768419467461829351372586289638715975

Wrap Up

Having done all this, I plugged my results into OEIS, and found this sequence whose description is the same as my problem except it cares only about the length of the sequence and not about its construction. The programs there to calculate it suggest some sort of counting argument that could maybe be converted into a construction but I’m not sure there’s enough detail for me to do so.