Siteswap Puzzles

First Attempt

In October, 2018, I had the idea to make a puzzle in the shape of a crossword puzzle where all the “words” are replaced by sitewaps. For more info on siteswap validation, I previously wrote a blog post on that topic. I tried to generate a solved puzzle by hand but had way more trouble than I expected.

I decided to use the only crossword generation tool I knew about - the one James Buckland wrote in response to a puzzle I gave him. His program takes a dictionary and generates all n x n squares such that all the rows and columns are valid words. All I had to do was generate a list of all siteswaps with length 6 and pass that in as the dictionary. This worked perfectly and I had a huge list of all valid 6x6 grids.

Now that I had all these solved puzzles, I needed to generate unsolved puzzles. I did some research on how sudoku are generated. Sudoku is a pretty mature puzzle so there are many answers but the simplest one looks like this:

start with a solved puzzle

for (cell in shuffled list of all cells):

clear that cell

if (modified puzzle doesn’t has a unique solution):

put the number back in that cell

This is pretty easy to implement, runs quickly, and is randomized enough that I don’t expect it to generate the same puzzle twice. All I had to do was implement as solution counter for partially solved puzzles.

I chose to represent the board as a 2d array a bitsets (representing cells) where biset.test(v) meant that v was a plausible value for that cell. My algorithm chose a cell with more than one possible value and created a candidate board as though that value was the only option. It also removed possibilities from the row/col of the modified cell that were no longer valid. Then for each board that wasn’t obviously invalid (some cell has 0 possibilities), it called itself recursively. I considered trying to pick unsolved cells in some clever way but the code already ran so quickly that it didn’t seem worth it.

I ended up publishing one of these puzzles to my instagram and was sent one correct solution. I chatted with the solver a bit and their opinions were really similar to mine - the novelty of the puzzle was fun but too much of the solve was tedious bookkeeping and not enough was clever inference. I decided that I’d had my fun with this project and mostly forgot about it for 5 month.

Variations

Out of nowhere, I realized that there are some valid sudoku solutions which are also valid in my puzzle. I decided to see if I could use this to make a more interesting second draft.

Generating a list of all siteswaps containing 1-9 exactly once was pretty easy and James’s tool would happily make me grids out of them. However, the tool didn’t have any built in way to handle the 3x3 block restrictions of sudoku. Rather that updating it, I decided to reuse some bits of my solver. I realized that generating a puzzle is exactly the same as solving a puzzle that as 0 cells filled in. Rather that early returning when more than one solution is found, my puzzle generator would early return the first time it found any solution will all cells filled in. One other difference from the earlier solver is that I iterated over possible values for a cell in random order. This was just in case iterating in value order introduced some bias. I’m not sure this matters but the overhead is so small that I don’t care.

The heart of my generator was a function called ConsiderBoard(). It took a board, the row and col of the cell to be changed, and the value to put in that cell - and it returned a new board where the constrained implied by putting that value into that row/col had been enforced. In this case there were 5 constraints:

- Sudoku rows

- Siteswap rows

- Sudoku columns

- Siteswap columns

- Sudoku 3x3 blocks

This meant placing each number could remove as many as 40 possible values from the board! Since possibilities were removed so quickly, board generation took a tiny fraction of a second.

My strategy here was the same as before - write a solution counter for unsolved puzzles and use it to remove values while keeping the solution unique. I did this mostly by reusing the ConsiderBoard() method.

As a fun side effect, that meant I could comment out the siteswap constraints and my program would generate unsolved sudoku puzzles. Or I could comment out the sudoku rules and my program would generate unsolved siteswap puzzle. Or any combination of constraints!

The first time I ran my reducer, the unsolved puzzle it spit out only had 4 numbers filled in. In retrospect this makes some sense. The more constraints I added, the smaller I made the number of legal solutions (to any puzzle); the fewer solutions exist, the fewer numbers are needed to specify each one.

Unfortunately, a puzzle with 4 numbers filled in is unapproachable for human solvers. I needed a way to stop reducing the puzzle once it had reached a goal difficulty.

I started by researching how sudoku difficulty is decided. The answer was much more interesting than I expected! AI solvers use a list of heuristics for inference and have a number of points associated with each one. Simpler ones cost fewer points to use than more complex ones. Once the AI has solved the puzzle, it counts up how many points it spent and what the most complicated inference technique was and uses those to assign a difficulty.

I considered something like this for my puzzle but decided it was too much work. In order to come up with the right heuristics and point values, I’d need to become an expert solver and I didn’t care enough. Instead I tried to think of a simpler solution that would be easier to implement.

I ended up writing a modified solver that picked cells at random and recorded how many guesses it took it to find the unique solution. Then, as I reduced from solved puzzle to unsolved one, I ran this random solver 100 times and took the mean of the number of guesses. This doesn’t look at all like how humans solve puzzles but the average number of guesses trended upward as pre-populated cells went away so it approximated something related to difficulty.

What I found was that the number of guesses sometimes had notable points where number of guesses jumped from <10 to >20. I tried to see if there was anything interesting about these points but didn’t think they were that different as a human. Also at some point the number of guesses max out at around 30 and stayed there as all remaining numbers were removed. As a human, I think these puzzles feel the most different in difficulty but the computer disagreed.

In the end, I decided that I’m only going to publish a few puzzles and I can just evaluate the difficulty by hand. If I were publishing a book of puzzle or something, I’d need to think a lot more critically about this.

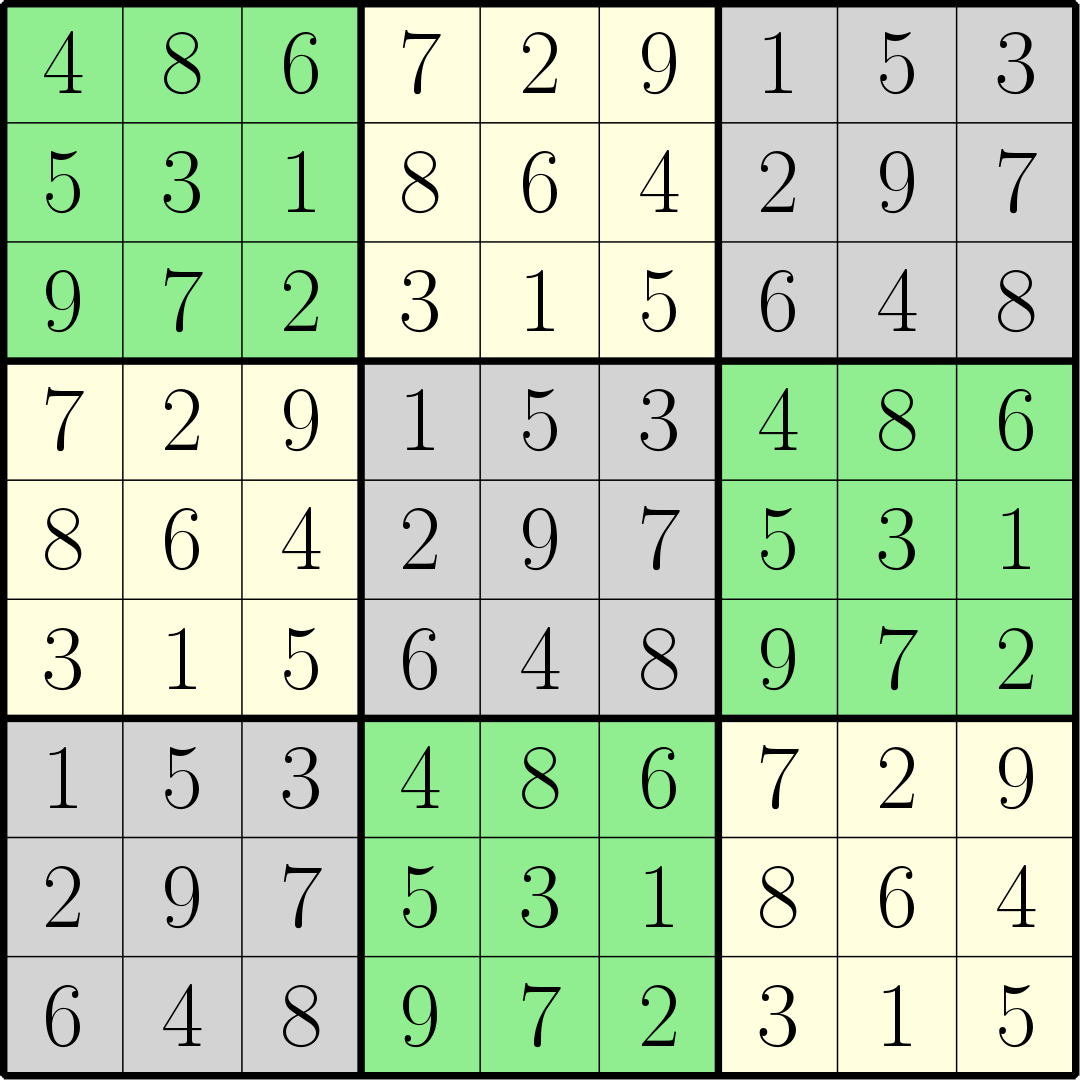

I asked my roommate to test one of the puzzles for me and he quickly spotted a pattern I hadn’t. I was so focused on how I expected the puzzle to be solved that I didn’t notice some recurring structure. In this case, {4,6,8}, {2,7,9}, and {1,3,5} always appeared contiguously in rows. In additon to that, {4,5,9}, {3,7,8}, and {1,2,6} always appear contiguously in columns. In fact, there are only 3 distinct 3x3 blocks in this solution.

Once I knew that this could happen, I found that it happened to a lesser degree pretty often. I never found a nice way to exclude solved puzzles with too much repition. Luckily, even with 100 solves with every number removed, my program still ran in under a second. I decided it was easier to just filter these out by hand. This is another thing I’d need to revisit if I were trying to publish more than a handful of puzzles.

So far, I’ve published 3 puzzles, an easy, a medium, and a hard, also to my instagram. All 3 are unsolvable if you only use sudoku type inference but have unique solution if you use both sudoku and siteswap rules. I’ve been mailed one correct solution to the easy puzzle. I also plan to publish another trio of puzzles with sudoku row/col rules removed but sudoku 3x3 cell rules still present. This is yet another novel solving experience that is worth trying once but probably not twice.